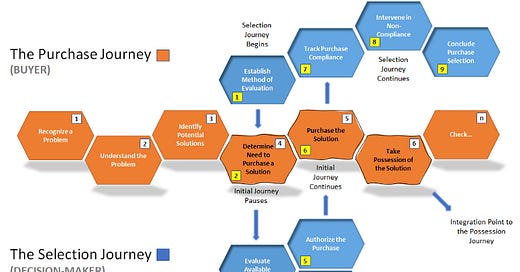

My Initial Layout of Customer Journey Integration

Remember: the end user is not always the customer on a journey

Remember: the end user is not always the customer on a journey

In my last piece I laid the groundwork for the 14 Customer Journeys necessary to understand customer experience completely. These 14 journeys are based on the list of consumption chain jobs found in Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI); although I have modified and added to them slightly. In Jobs-to-be-Done, the Job and each Step are designed to describe an objective, or an achievement. They are also named in a very similar fashion best practices found in the process modeling world. And one more thing, they do not use mushy words that are inconsistently defined.

A process guru’s take on using mushy words:

“They are easy to use, so they give the illusion that progress is being made, but they really don’t tell us anything. In other words, what is actually “achieved” when we use the term Monitor Shipment, Administer Application, and Track Project?” — Sharp & McDermott (2009)

While ODI does not always map out consumption chain jobs wh…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Practical Innovator's Guide to Customer-Centric Growth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.